A common problem seen in DOAJ applications is endogeny, i.e., editorial board members publishing too often in their own journals. In this guest post, Maryna Nazarovets and Serhii Nazarovets discuss the related idea of editorial endogamy and how university journal publishers can uphold editorial independence and avoid nepotism.

University journals often start their journey to DOAJ full of energy and optimism, with a complete website redesign, updated policies, and well-formatted metadata. Everything seems to be running smoothly and the application is expected to be approved without any major issues. Yet obstacles specific to university publishing, which are rarely considered in advance, unexpectedly arise. These challenges can slow down, or even halt, the process of inclusion in DOAJ. Many editorial teams aren’t even aware that these obstacles exist until they begin preparing their application.

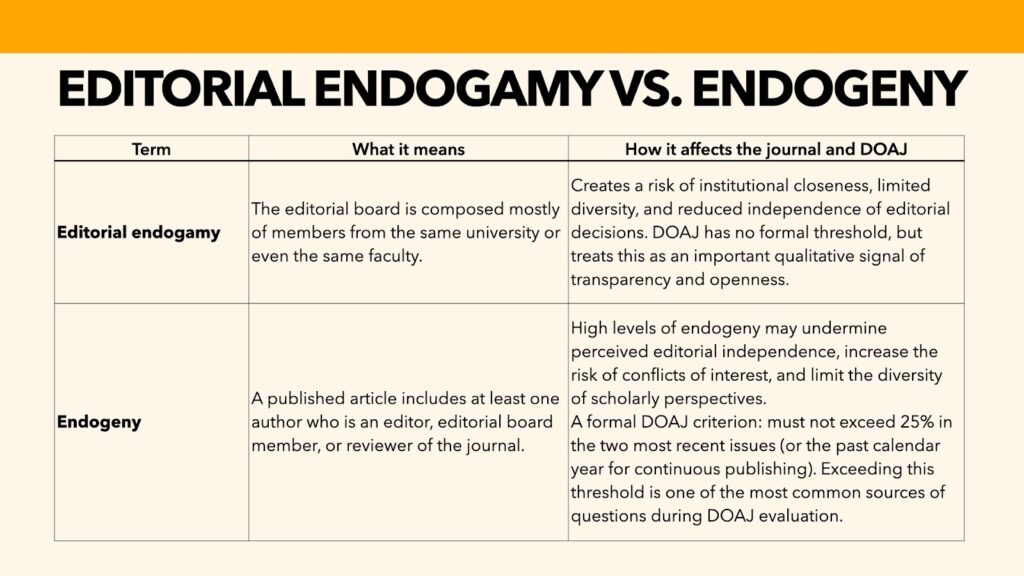

It’s often at this stage that journals realise that their editorial board is composed almost entirely of colleagues from the same university that publishes the journal. This phenomenon, known as editorial endogamy, raises concerns about the independence of editorial decisions. If the editor-in-chief, deputy editors, editorial board members, and technical editors all, or the majority of them, come from the same university or faculty, the risk of institutional influence grows. The DOAJ Guide to Applying explicitly recommends avoiding situations where all members of the editorial board come from the same institution.

In our recent article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-025-09687-z), we show that endogamy is not an individual problem of a single journal, but a systemic, interregional pattern in university publishing. Editorial roles at university journals are often perceived as internal university positions: editorial board seats are allocated through local academic networks, institutional loyalty, and career incentives, rather than through open and competitive selection. Without consistent ethical or organisational oversight, this practice gradually becomes normalised. In some regions, it’s reinforced by local academic culture. In countries where university journals are involved in reporting or career decisions, the editorial structures are often kept under the control of the institution and sometimes under administrative pressure.

DOAJ, meanwhile, adds another important term – endogeny – and incorporates it into its journal selection criteria. This refers to situations where more than 25% of articles in the two most recent issues (or in the past calendar year for continuous publishing) include at least one author who is an editor, editorial board member, or reviewer of the journal. The threshold is far from strict, yet it’s still often exceeded by university journals – not because they’re dishonest, but because the way local academic ecosystems are set up makes internal publishing more common.

Figure 1: Editorial Endogamy vs. Endogeny. Definition and DOAJ Guidelines

Most university publications operate with very limited resources and are frequently subject to administrative pressure. Building a diverse editorial portfolio is no easy task. At the same time, publishing in the institutional journal is usually simple and predictable for university staff, which naturally encourages internal submissions. The low flow of external submissions, given the journal’s modest visibility and prestige, makes it difficult to widen the author base. In such circumstances, it’s natural that editors occasionally publish in “their” journal. When this happens for years, the proportion of endogenous articles gradually increases.

Although editorial endogamy and article endogeny are closely related, they aren’t identical. Endogamy often creates structural conditions that make endogeny more likely, but it doesn’t automatically lead to it. Conversely, endogeny may appear even in journals with a more diverse editorial board composition.

Both phenomena, whether occurring together or separately, tend to reinforce a dynamic that transforms the journal into a local information platform. Over time, this dynamic begins to work against the journal itself, even if it operates openly and transparently: the diversity of research topics declines, the search for high-quality reviewers becomes more difficult, and external trust decreases. The academic community expects journals to be inclusive, independent, and oriented toward a broad readership.

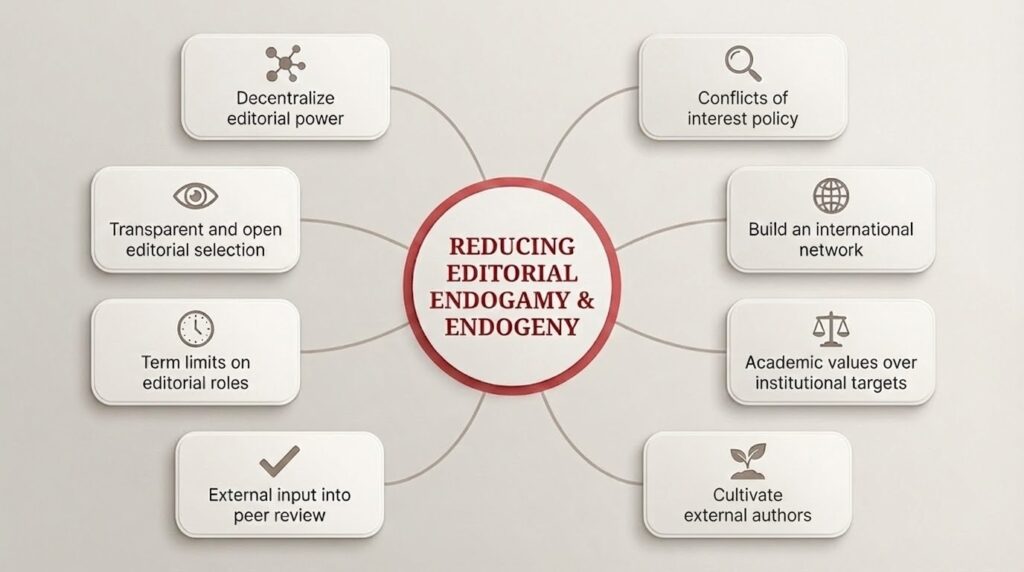

Figure 2. Reducing Editorial Endogamy & Endogeny (Image created in Google Slides by Matt Hodgkinson)

To shift their trajectory, university journals may need to rethink their editorial practices and management structures. Below, we offer a far-from-comprehensive list of possible measures that could help reduce endogamy and endogeny in university publishing:

1. Decentralise power in the editorial structure:

- avoid situations where the entire board comes from one department or institution and a representative of the university administration plays a leading role

- involve colleagues from other institutions and countries not “for balance” but for real engagement in the process

- regularly revise the composition of the editorial board

- clearly define the roles and responsibilities of all editors

2. Introduce a transparent and open system for editorial selection:

- announce open calls for new editors

- apply clear selection criteria (such as review experience, disciplinary expertise, understanding of publication ethics, etc.)

- editors substantive responsibilities rather than symbolic status

3. Avoid “lifetime” appointments:

- define terms (for example, three to four years) with the possibility of limited re-election

4. Ensure meaningful external input into the peer review process:

- avoid situations where most reviewers are employed by the publishing university

- actively build an international pool of reviewers

- explore transparent peer review models that fit the journal’s disciplinary context

5. Cultivate a culture of external author submissions:

- clear calls for papers targeting external authors

- strengthen inter-institutional communication

- encourage editors to promote the journal at international events

- no privileges for “in-house” authors

6. Document, publish, and follow policies on conflicts of interest:

- how authors’ and editors’ contributions are processed

- who makes decisions in cases of potential conflicts

- how the independence of peer review is ensured

7. Promote the journal as an academic platform rather than a tool for local targets:

- explain to the university administration that this model damages the reputation of the journal and the university as a whole

- suggest alternative reporting mechanisms that don’t rely on the journal

8. Build an international network of partnerships:

- invite external experts to join the editorial board

- establish collaborations with other journals and universities

- produce joint special issues

- exchange editorial practices and peer reviewers

Endogamy and endogeny aren’t a death sentence for a university journal. Instead, they offer a mirror that helps identify where the editorial team can become more open, diverse, and balanced. University journals play a key role in the development of open science, and they are often strong examples of sustainable, independent, diamond OA initiatives. Therefore, demonstrating that a journal operates transparently and independently is an important and entirely achievable step.

Maryna Nazarovets is a research fellow in TIB – Leibniz Information Centre for Science and Technology (Hanover, Germany). She specialises in scholarly communication, journal publishing, editorial practises and evaluation of publication activity. Mastodon Facebook LinkedIn

Serhii Nazarovets is a senior researcher in scientometrics and scholarly communication at Borys Grinchenko Kyiv Metropolitan University (Kyiv, Ukraine). His work focuses on research evaluation, open science, and the transparency and integrity of scholarly publishing practices. Mastodon Bluesky Facebook LinkedIn

This is a very interesting and necessary topic, and the blog post explains it in a clear and precise way. That said, there are three additional aspects that could be worth discussing, especially regarding endogeny:

1. Broader criteria in some databases: Several indexing databases consider endogeny not only when editors publish in their own journals, but also when authors from the same institution as the journal publisher contribute frequently—even if they are not part of the editorial team or reviewers. This expands the scope beyond the DOAJ definition.

2. Impact of institutional size and editorial policy: A large university or a strict editorial policy can make it easier to ensure that an author affiliated with the publishing institution has no influence on the acceptance of their article, particularly when reviewers are external.

3. Association-based governance: Endogeny can also arise when a journal is formally published by a university but is effectively managed by an academic association whose members come from multiple universities. In such cases, authors’ membership in the association is not disclosed in articles, yet this relationship may create similar effects to those discussed under editorial endogamy.